Modular 101: Code First (Part 1) How Code Compliance is Verified in Modular Construction

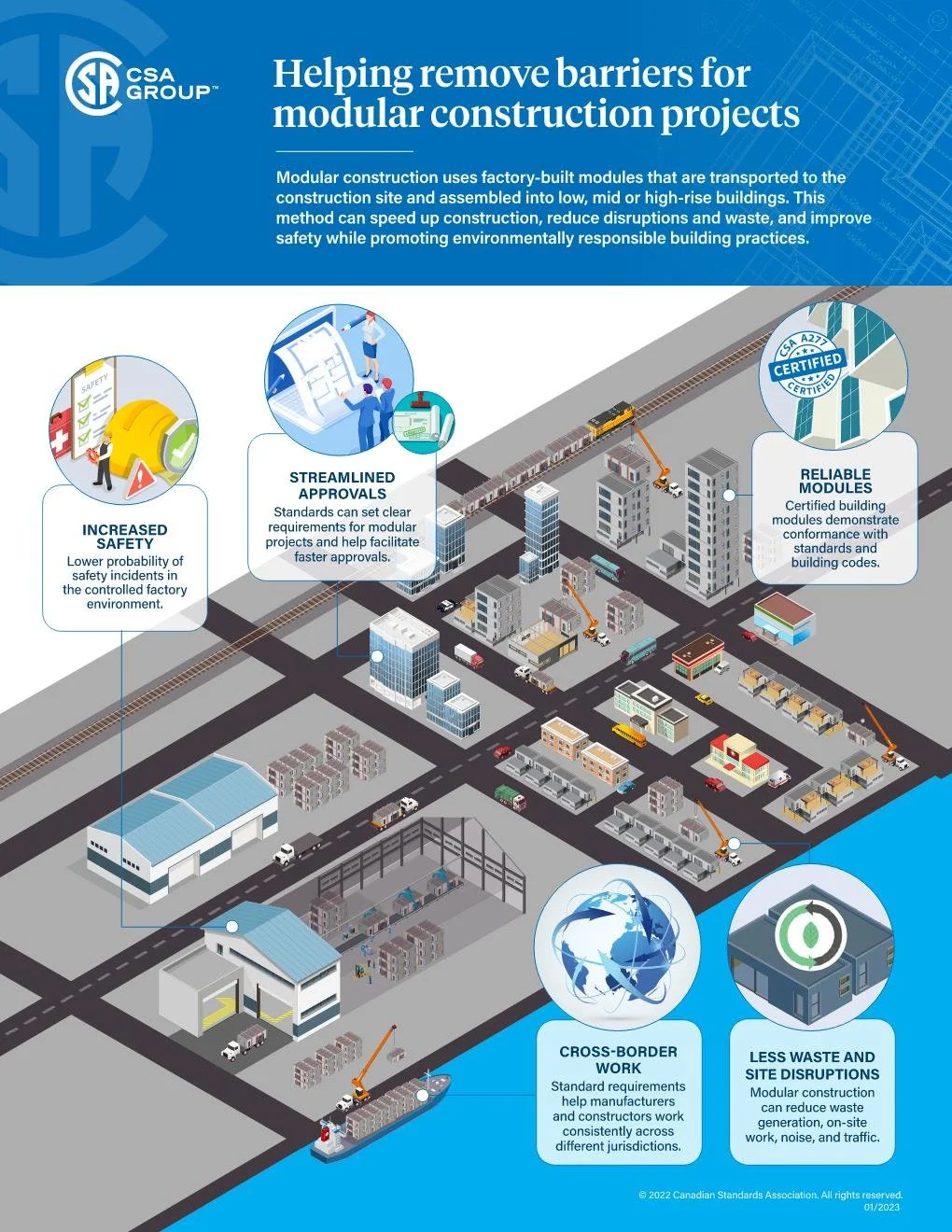

Modular construction is not exempt from building code compliance, but it is held to the same performance and safety standards as conventional construction. However, the way compliance is demonstrated, verified, and enforced differs significantly. Understanding these procedural and jurisdictional differences is not optional for architects practicing in Ontario or elsewhere in Canada; it is a prerequisite for competent design and contract coordination.

This two-part series examines the regulatory mechanics of modular code compliance. Part 1 focuses on how the Ontario Building Code (OBC) and CSA A277 certification interact, where inspection authority is divided, and what happens during factory and site verification. Part 2 will address matelines, permit workflows, and the failure modes that emerge when coordination breaks down.

The Code Applies, But Verification is Split

The Ontario Building Code applies in full to modular buildings. There is no "modular exception." A six-storey modular apartment building must meet the same fire separation, exiting, structural, and envelope performance requirements as a conventionally-built equivalent under OBC Part 3.

What changes is where and when compliance is verified.

In conventional construction, the Authority Having Jurisdiction (AHJ), typically a municipal building official, conducts on-site inspections at key stages: footings, framing, rough-in, and final. The inspector sees the building as it is built, in sequence, and can issue deficiency notices before work proceeds.

In modular construction, much of the building is constructed in a factory, often hundreds of kilometres from the installation site. The AHJ may never see the module interiors. Verification must occur in two places:

Factory verification: conducted during manufacturing, either by a third-party certifier under CSA A277 or (rarely) by the AHJ directly

Site verification: conducted after module delivery, covering foundations, structural connections, and assembly interfaces

This division creates procedural complexity. If factory inspection is inadequate, site inspectors cannot verify concealed work. If site assembly deviates from approved drawings, factory certification may become irrelevant.

CSA A277: What It Certifies (and What It Doesn't)

CSA A277 (Procedure for Certification of Prefabricated Buildings, Modules, and Panels) is the Canadian standard for third-party certification of factory-built modules. It establishes a quality assurance framework that allows accredited certification bodies to verify code compliance during manufacturing.

What CSA A277 Certification Confirms

A CSA A277-certified module has been produced in a factory whose quality assurance and quality control (QA/QC) process has been audited and approved by a third-party certifier. The certification confirms that:

The factory has documented QA/QC procedures for structural framing, fire-rated assemblies, MEP rough-ins, and envelope construction

Factory personnel are trained and competent to execute these procedures

The factory maintains inspection records, material certifications, and assembly documentation

The specific project's design drawings have been reviewed for code compliance

The factory's internal inspections confirm the modules were built according to the certified process

The module receives a certification label, often a sticker, affixed to the unit to confirm compliance at the time of manufacture.

What CSA A277 Does Not Certify

CSA A277 does not certify:

Site-specific conditions: foundation design, geotechnical compliance, zoning conformance

On-site assembly: module-to-module connections, mateline fire-stopping, structural tie-downs

Building systems integration: HVAC distribution across modules, plumbing risers, fire alarm continuity

Transportation damage: modules may be damaged in transit; certification does not extend to post-delivery condition

Critically, CSA A277 does not replace the building permit or relieve the architect of record of their code compliance responsibilities. It is a factory quality control mechanism, not a substitute for design coordination or site inspection.

OBC Part 3 vs Part 9: Procedural Implications for Modular

The distinction between OBC Part 3 (Large Buildings) and Part 9 (Housing and Small Buildings) is not just about which code provisions apply. It also affects inspection logistics, documentation requirements, and designer liability.

Part 3 Buildings: Objective-Based Compliance

OBC Part 3 applies to buildings with a building area exceeding 600 m² or a building height exceeding three storeys. Compliance is objective-based, requiring coordination across multiple disciplines:

Fire safety design (exiting, fire separations, sprinkler systems)

Structural design (sealed by a Professional Engineer)

Building envelope design (thermal, air, and vapour control)

Mechanical and plumbing systems (ventilation, drainage, energy recovery)

For Part 3 modular buildings, design professional involvement is mandatory. Architects and engineers must seal drawings, and their professional liability extends to factory-built components. The certifier reviews modules against these sealed drawings, but the designer remains responsible for ensuring the drawings comply with the code.

Part 9 Buildings: Prescriptive Compliance

OBC Part 9 applies to smaller buildings, typically houses, duplexes, and low-rise residential under the Part 3 thresholds. Part 9 is prescriptive, specifying acceptable solutions (e.g., minimum stud spacing, insulation R-values, window-to-floor-area ratios).

For Part 9 modular buildings, compliance is often more straightforward, but factory certification may be less common. Some manufacturers produce Part 9 modules without CSA A277 certification, relying instead on factory-based municipal inspection or treating modules as "prefabricated assemblies" under Part 9 provisions.

This creates variability. Not all Ontario municipalities treat Part 9 modular the same way. Some require factory certification; others do not. Architects must confirm AHJ expectations early.

Factory Inspection Protocols: What Actually Happens

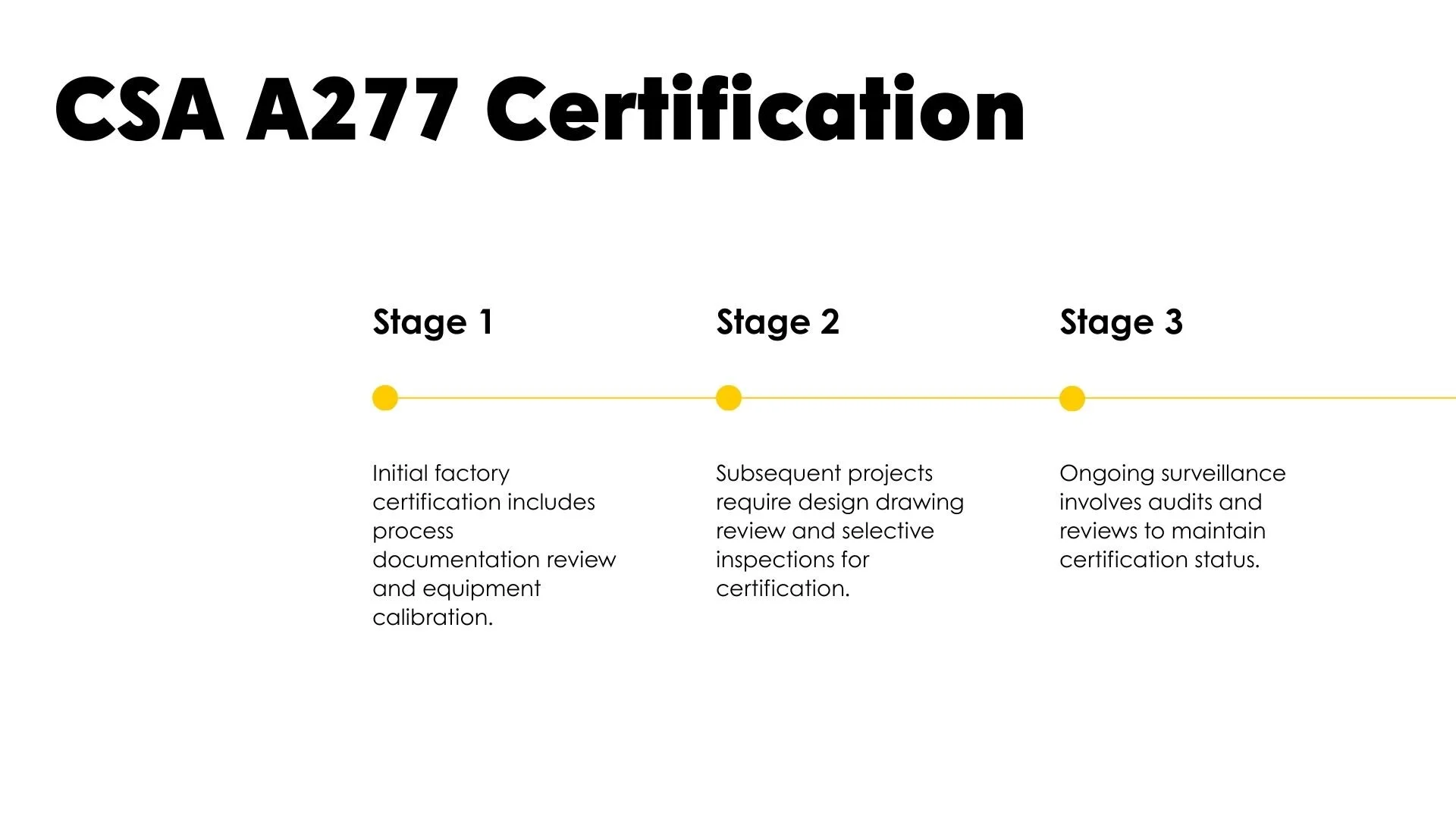

CSA A277 certification is fundamentally different from site-based inspection. It certifies the factory's quality assurance and quality control (QA/QC) process, not individual projects. This distinction is critical for architects to understand, as it changes expectations around inspection frequency, documentation requirements, and certification scope.

Initial Factory Certification: Full Process Audit

When a factory first pursues CSA A277 certification, the third-party certifier conducts a comprehensive audit of the facility's QA/QC procedures. This includes:

Process documentation review: Standard operating procedures, inspection checklists, material tracking systems, and quality control protocols

Personnel qualifications: Verification that factory staff are trained and competent to execute the documented procedures

Equipment calibration: Confirmation that measurement and testing equipment is properly maintained

Full project inspection: A complete inspection of a representative project, including all hold points (framing, rough-in, insulation, fire-rated assemblies, final), to verify that the factory can execute its documented process

Once the certifier confirms that the factory's QA/QC process can produce code-compliant modules, the factory is certified, not the individual project. The assumption is that the factory will follow the same documented procedures for all subsequent projects.

Subsequent Project Certification: Desktop Review and Sampling

For projects produced after initial factory certification, the inspection approach changes. Third-party certifiers typically conduct:

Design drawing review: All architectural, structural, mechanical, electrical, and plumbing drawings are reviewed for code compliance before production begins

Desktop review of QA/QC records: The factory's internal inspection records, material certifications, and assembly logs are reviewed to confirm that the certified process has been followed

Selective site inspections: Depending on project complexity and scale, the certifier may conduct limited factory visits, but not necessarily at every production milestone

For smaller projects, certification may be completed entirely through desktop review of the factory's QA/QC documentation, with no physical inspection of the specific project's modules. The certifier relies on the factory's internal quality control and documented compliance with the certified process.

Ongoing Factory Surveillance: Semi-Annual or Annual Audits

To maintain CSA A277 certification, factories undergo surveillance audits conducted by the third-party certifier semiannually or annually. During these audits:

The certifier reviews whatever project is in production at the time of the visit

The factory's QA/QC records are audited to confirm that the certified process is being followed

Any deviations from the certified process must be identified and must be corrected

If non-conformances are found, the factory may be required to implement corrective actions or face suspension of certification

Large or Long-Duration Projects: Multiple Inspections

For projects large enough to span multiple production cycles or that remain in production for a year or longer, the certifier may conduct multiple inspections across different production phases. This provides sampling across the project timeline to confirm consistent adherence to the process.

However, even in these cases, the certifier is not inspecting every module or every milestone. They are sampling to verify that the factory's certified QA/QC process remains in place.

Architect's Role in Factory Certification Coordination

Given this certification structure, architects must understand that:

CSA A277 relies on factory self-inspection: The factory's internal QA/QC is the primary mechanism for ensuring code compliance. The third-party certifier audits the process, not the product.

Design drawing review is critical: Since certifiers review drawings before production begins, incomplete or ambiguous details can delay certification. The factory cannot begin production until the certifier approves the design package.

Factory QA/QC documentation must be contractually required: If the factory does not maintain rigorous internal inspection records, desktop reviews will fail. Architects should specify QA/QC documentation requirements in contract documents.

Site-specific attendance at third-party inspections may not be possible: Unlike conventional construction, where architects can request inspections at specific times, factory surveillance audits occur on the certifier's schedule, not the project schedule. Architects may not have the opportunity to attend third-party inspections for their specific project.

Certification does not guarantee zero defects: Because certification relies on process compliance rather than 100% inspection, defects can still occur. Transportation damage, material substitutions, or production errors may not be caught before modules ship.

Factory Site Visits: Recommended Practice

While third-party certification operates independently of the architect's attendance at project-specific architect meetings, factory site visits by the architect during production are strongly recommended. These visits serve multiple purposes beyond inspection:

Process familiarity: Architects gain direct exposure to the factory environment, production sequencing, and manufacturing constraints that cannot be fully understood from drawings alone

Multi-stage review: Unlike conventional construction, where inspections occur sequentially over weeks or months, factory production allows architects to observe modules at different stages of completion simultaneously. In a single visit, an architect can review framing on one module, rough-in MEP on another, and finished millwork on a third.

Coordination verification: Architects can identify coordination issues, such as conflicts between trades, material substitutions, or deviations from design intent, before modules ship, when corrections are still feasible

Relationship building: Direct engagement with factory personnel builds communication channels that are critical when shop drawing questions or field issues arise later in the project

Factory visits do not need to occur as frequently as conventional site reviews. For most projects, one or two strategically timed visits, early in production to verify setup and coordination, and mid-to-late in production to review near-completion quality, are sufficient. However, these visits should be planned in advance and coordinated with the factory's production schedule to maximize value.

Contractually, architects should negotiate the right to conduct factory visits and should clarify whether travel costs are reimbursable or included in the fee structure. Some manufacturers welcome architect visits; others view them as disruptive. Establishing expectations early prevents friction during production.

Site Inspection: What the AHJ Verifies

Once modules arrive on site, the AHJ conducts inspections to verify:

Foundation compliance: Footings, grade beams, and anchor bolts must meet structural drawings and OBC requirements

Module placement and alignment: Modules must be installed per the approved site plan and foundation layout

Structural connections: Module-to-module tie-downs, lateral bracing, and shear connections must be installed and inspected

Mateline fire-stopping and sealing: Fire-rated joints between modules must be sealed with approved materials and methods

Building services integration: HVAC ductwork, plumbing risers, electrical feeders, and fire alarm wiring must be connected and tested

The site inspector does not inspect the interior of modules, as that work has already been certified at the factory. However, if the site inspector suspects damage during transport or improper installation, they may request access to module interiors or additional documentation.

This is where the division of responsibility becomes critical. The factory certifier has verified that modules left the factory in compliance. The site inspector verifies that modules arrived intact and were assembled correctly. If either party fails in their verification role, the building may not achieve code compliance and the architect is left managing the deficiency.

Conclusion

Understanding how code compliance is verified in modular construction is not optional—it is foundational. The OBC applies in full, but verification is distributed across factory certification, third-party audits, and site inspection. CSA A277 provides a framework for factory QA/QC, but it does not replace the architect's responsibility to coordinate design, documentation, and enforcement.

Part 2 of this series will examine where this system is most vulnerable: matelines, permit workflows, and the specific failure modes that occur when coordination breaks down. These are the technical challenges that separate competent modular practice from projects that fail inspection, delay occupancy, or compromise safety.

•••

XLBench is your go-to platform for modular construction insights, setting industry benchmarks, fostering expert discussions, and sharing the latest trends. Through Benchboard, we provide data-driven research, thought leadership, and in-depth analysis to advance modular innovation.

Stay informed and be part of the conversation—follow XLBench for the latest updates, expert insights, and industry trends.

•••

xL Architecture & Modular Design (XLA) is an innovative architecture firm redefining the future of building through off-site construction technologies. With expertise in volumetric modular designs, and panelized building systems, we create cutting-edge solutions that seamlessly integrate form, function, and sustainability.