Modular Construction Needs Modular Contracts Part 1: Why Legal Structure Matters More Than Ever

Introduction: Contracts as a Hidden Constraint in Modular Construction

As modular construction continues to gain traction across North America, discussions often focus on speed, cost certainty, factory efficiency, and quality control. Yet one of the most persistent barriers to scaling modular construction remains largely invisible: the legal contracts governing how modular projects are delivered.

Modular construction fundamentally alters the traditional construction sequence. Design decisions must be finalized earlier, construction begins in a factory rather than on site, and financial risk shifts forward in the project timeline. However, in Canada, most modular projects are still delivered using standard contracts originally written for conventional site-built construction. The result is a growing mismatch between how modular projects actually function and how risk, responsibility, and payment are contractually defined.

In contrast, the American Institute of Architects (AIA) released a dedicated Volumetric Modular Construction (VMC) Contracts last year in 2025, supported by a family of contract documents explicitly tailored to factory-built construction. This move signals a level of contractual maturity that the Canadian modular industry has yet to reach.

This first part of the XLBench series examines why contracts matter in modular delivery and compares the legal structure of the AIA VMC framework with Canada’s commonly used CCDC 14, CCDC 15, and also architecture association’s contracts like OAA 600.

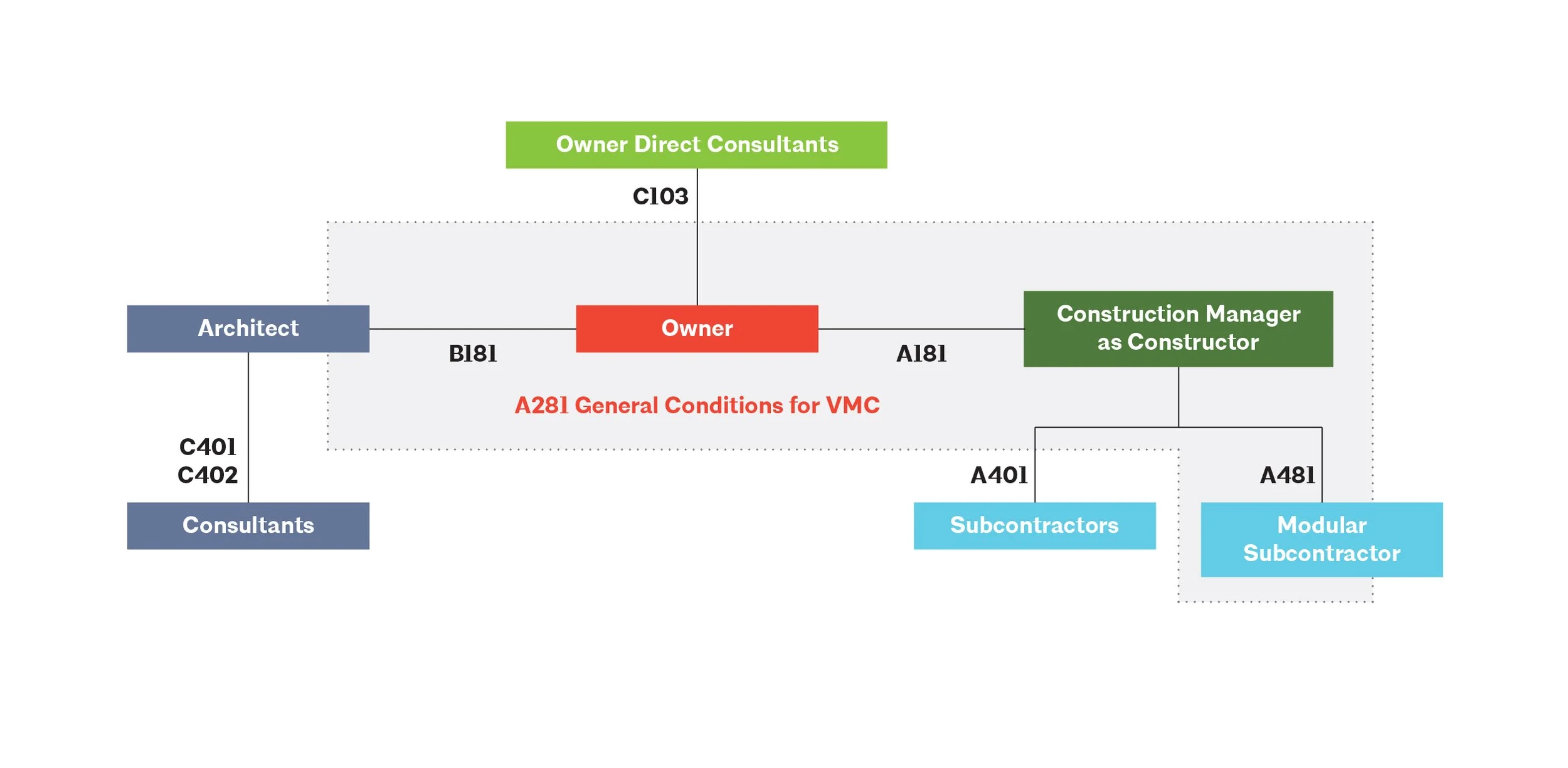

Understanding the AIA Volumetric Modular Construction Framework

The AIA VMC Contracts are not merely a modified version of existing construction contracts. It represents a fundamental rethinking of project delivery in recognition of how volumetric modular construction actually works.

At the core of the AIA approach is the acknowledgement that manufacturing is construction, and that the factory must be treated as a legitimate construction site. The VMC framework explicitly addresses issues unique to modular delivery, including design freeze, off-site quality control, transportation risk, storage, sequencing, and the relationship between factory work and on-site assembly.

Key characteristics of the AIA VMC framework include:

Explicit recognition of the factory as a construction site

Clear delineation of roles between architect, modular manufacturer, and constructor

Contractual recognition of design freeze prior to fabrication

Defined milestones tied to manufacturing progress, not just site progress

Allocation of risk during fabrication, transport, and staging

Rather than forcing modular projects into a site-built legal framework, the AIA contracts are structured to reflect the realities of industrialized building delivery. This distinction becomes especially important when comparing them to Canadian contract models.

More details of the AIA VMC framework, including key term definitions, can be found on the Guide to AIA Volumetric Modular Construction Documents.

Image Credit: AIA

The Canadian Landscape: CCDC 14, CCDC 15, and OAA 600

In Canada, modular projects are most commonly delivered under CCDC 14 (Design-Build), often supplemented by CCDC 15 for design services and OAA 600 for consultant roles. These contracts are widely used, well understood by lenders and insurers, and deeply embedded in the Canadian construction ecosystem.

However, none of these documents were developed with factory-based construction in mind.

CCDC 14 assumes a construction process where work progresses sequentially on site, design development can continue during construction, and field instructions or substitutions can be issued when conditions change. This assumption is fundamentally incompatible with volumetric modular construction, where most decisions must be finalized before fabrication begins and late-stage changes are either impossible or extremely costly.

CCDC 15 and OAA 600 further reinforce this misalignment. Consultant agreements assume a traditional design-bid-build or design-build process where consultants remain engaged throughout construction to respond to site conditions. In modular projects, much of the “construction” happens before consultants would traditionally issue construction-phase services, creating gaps in responsibility, liability, and scope definition.

Comparing Legal Structures: Integrated vs Fragmented Frameworks

One of the most significant differences between the AIA VMC contracts and Canadian CCDC/OAA agreements lies in their legal structure.

The AIA VMC framework is designed as an integrated system. It anticipates the presence of a modular manufacturer as a distinct and essential project participant, not merely a subcontractor. Responsibilities related to design coordination, manufacturing quality, transportation, and installation are explicitly addressed, reducing ambiguity and overlap.

By contrast, Canadian modular projects often rely on fragmented agreements. The modular manufacturer may be engaged as a subcontractor under a general contractor, while consultants are retained under agreements that do not reflect the realities of manufacturing-driven delivery. This fragmentation creates uncertainty around who is responsible for coordination failures, manufacturing errors, or schedule impacts arising before site work begins.

Another key distinction is the treatment of timing. The AIA VMC framework recognizes that risk and cost are incurred earlier in modular projects and structures contractual obligations accordingly. Canadian contracts continue to anchor responsibility and payment milestones to site-based activities, even when most of the project value has already been committed in the factory.

Why This Matters

Contracts do more than allocate risk. They shape behaviour, influence financing, and determine whether modular construction can scale beyond one-off projects. When legal structures fail to reflect how modular projects actually function, inefficiencies and disputes become inevitable.

Part 1 of this series highlights a growing gap between contractual frameworks in the United States and Canada. While the AIA has moved decisively to address volumetric modular delivery through purpose-built contracts, Canada continues to rely on documents that assume a site-built paradigm.

In Part 2, we will examine how this structural misalignment plays out in practice, focusing on responsibility and liability gaps, financial and payment challenges, what Canadian contracts currently lack, and who ultimately holds responsibility for evolving the CCDC framework to better support the modular industry.